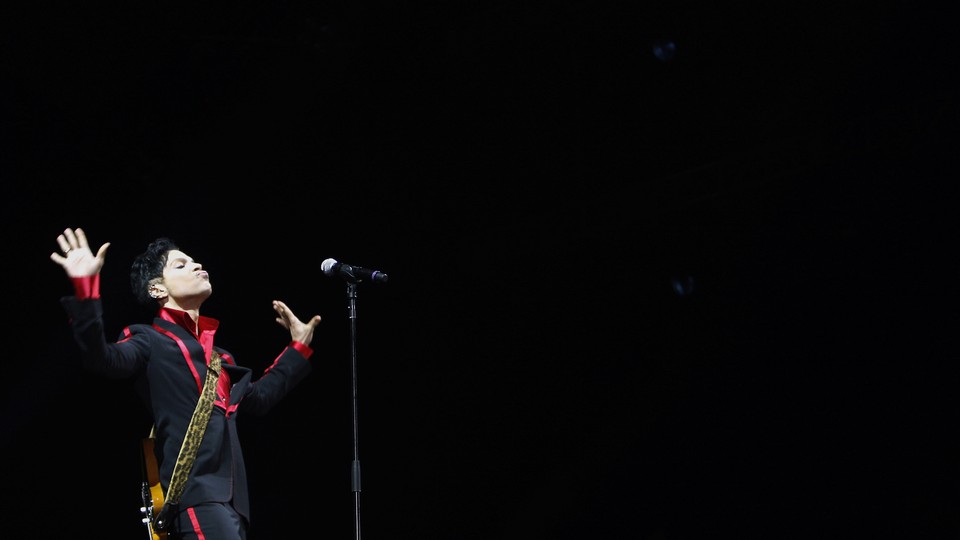

Should Prince's Tweets Be in a Museum?

Archivists are figuring out which pieces of artists’ digital lives to preserve alongside letters, sketchbooks, and scribbled-on napkins.

Even two months after his death, Prince’s Twitter feed has 330k followers. Aside from a subtle profile-picture replacement following his overdose—from an illustration of him wearing sunglasses to one with his eyes closed, but a third eye open—his feed remains stuck in time and precisely what anyone familiar with him would expect it to be. It follows nobody. The tweets are full of exclamation points, spirituality, capital letters, emoji, pictures of himself and purple objects, expressions of love for other artists, and quotes—not retweets—of fans praising him.

@benni1028What did u do 2 us in Atlanta, @Prince? I've barely slept since that nite. #FeelingRejuvenated #FeelingInspired #FeelingLoved

— Prince (@prince) April 17, 2016

Eventually, Twitter will delete Prince’s account—although a representative from the company couldn’t provide specifics as to how long any inactive account lasts before permanent removal. When this happens, it won’t just be the words of the 740 tweets Prince posted that get lost, but traces of his social-media behavior and routine. Any record of communications he sent or received will vanish. Deleting a known figure’s—or anyone’s account—erases an extension of themselves, part of what makes up their online footprint.

Should famous artists’ social-media profiles be saved? Archiving their digital materials would follow the tradition of old-school paper archives, the ones that are responsible for maintaining collections like hundreds of Emily Dickinson’s letters, notes from Mary Shelley that show her succumbing to a brain tumor, and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s working drafts and photographs. If journals, sketchbooks, letters, and scribbled-on napkins are venerated and kept for insights into great minds, there seems to be a case that tweets should be held onto, too. Then again, publicly accessible 140-character bursts can be so frivolous—and based so much on maintaining appearances—that they might seem like they don’t offer anything worth preserving.

In an archive, a writer’s correspondences are always separated from their manuscripts, business papers, and any other categories archivists create to organize their collection. The process prevents letters from being collated along with professional pieces. If tweets are to be considered as important as letters and the other kinds of casual scrawlings that end up exhibited in library or museum display cases, the medium still demands its own set regulations and expectations. Archivists now have the challenge of working through the kinks of determining digital material’s place among artists’ greater estates and settling on a feed’s value.

In 2005, biographer Gerald Clarke compiled and published Too Brief a Treat: The Letters of Truman Capote, a collection that spans from the 1930s to the 1980s—Capote died in 1984—and includes private letters, telegrams, and postcards to fellow writers, celebrities, editors, and artists, such as Richard Avedon, Jackie Kennedy, Tennessee Williams, and Audrey Hepburn. There’s good reason to publish these documents. Having that type of VIP access to a writer’s mind can inspire new interpretations of their work and reveal things that have gone unspoken in their lives. Capote might have wanted his papers to stay under wraps, but the language is so rich, the gossip so juicy, and the imagery so colorful that each letter reads like best-selling literature.

The literary value isn’t as clear on a platform like Twitter. Even with Capote’s skill, the character limit would force him to translate his style to fit the form. Would Twitter’s confines turn his writing turn average and unrecognizable?

Last year three prominent Twitter users passed away: Lisa Bonchek Adams, a writer; David Carr, a journalist at The New York Times; and Harris Wittels, a comedian. Their accounts are still online, inactive—minus a brief takeover of Carr’s account by a pornbot named Miranda back in May—and have a total of 561K followers between them. The three feeds act as case studies for predicting tweets’ longevity. On one side of the spectrum is Adams’ feed, naked and raw as she shared the intricacies of battling cancer. Carr’s feed is almost entirely reactionary, full of urls and best-suited to appear interspersed among the digital landscape it critiqued. Somewhere between is Harris Wittels’ account; many of his tweets have a similar timeless quality as Adams’, while others already prompt head scratching and googling just a year or so later.

After Wittels’ death last year, his fans and friends retweeted their favorites, reviving his finest Twitter moments in memoriam. But there are already videos of his standup and performances, podcasts where he appeared as a guest, a book based on his #Humblebrag Twitter side project, and a litany of writing credits on popular TV shows. Does his feed really provide anything that his professional portfolio does not?

“Diaries are full of mundane details, like what a person ate for breakfast, in the same way that Instagram can capture that with a photo,” says Michele Filgate, a New York-based writer whose 2013 Salon article “Will Social Media Kill Writers’ Diaries” considers the public turn of writers’ personal reflections. It’s not that Twitter has replaced traditional records, she tells me; Twitter has translated them for the internet age. “Social media has given writers new opportunities to connect with their readers. [It] has become another part of what writers leave behind, and especially in [Adams’] case. Her words live on through her blog posts and through her Twitter feed. That's part of her legacy.”

Whether a Twitter account is merely a reminder of an artist’s existence on the platform, demonstrates their mastery of a new medium separate from their professional output, or is a brand account that reads more like a PR statement than like a diary, a feed is a neatly packaged trove of their daily interactions with the world. In 50 years, it won’t matter whether a famous writer thought the dress was blue, but the fact that they chose to comment on something so minor adds nuance to their public persona and shows their position within the conversations of the day.

“There's a beauty to that mixture of mundane and more serious thoughts,” says Fligate. “There's a permanence, even though it seems like a fleeting moment.”

At the same time, the notion of isolating a Twitter feed from the surrounding noise generated by the 24-hour news cycle, content churn, and the other 310 million active users poses its own set of problems for archivists. Aside from a general knowledge about the service, and the legal complications regarding Twitter’s ownership of what’s published on the site, “there’s this whole insider culture you have to understand,” says Julie Swierczek, a librarian at Swarthmore College and formerly a digital archivist at Harvard Art Museums. Hashtags, for instance, she says, can be used ironically, to participate in a game or conversation, to express solidarity with a movement—like #BlackLivesMatter—or to react to a meme or fandom culture—like #WinterIsComing. A single tweet with a trending hashtag lacks the context of its associated online community or discussion.

There’s also the headache of Twitter-specific jargon and practices like mentioning a brand or individual by Twitter handle. Letters are exclusive; one person writes to another, and generally, the relationship is clear. But mapping of an artist’s contacts through Twitter feeds would be like trying to untangle thousands of yarn spools after bored cats unraveled them in a cluttered studio apartment. People tag celebrities, politicians, and brands as a joke, to pick a fight, demonstrate agreement, attribute a quote, or praise a new product.

Swierczek calls social-media platforms the “Wild West” of the archiving world. Suddenly researchers have to invent new guidelines for future protocol, as well as new tools and databases. Swierczek compares this new demand to what must have happened with the invention of the printing press.

In 2010, the Library of Congress, in partnership with Twitter, began the process of archiving all tweets published from 2006 to 2010, with the intention of one day opening up the resource to researchers with the belief that “social media is supplementing, and in some cases supplanting, letters, journals, serial publications and other sources routinely collected by research libraries.”

If this initiative ever comes to fruition, that too will require explorative trial and error before the collection can serve any greater purpose. Even if every tweet were saved, “you can’t keyword search … so you’ll just have a mass of billions of billions of tweets,” Swierczek explains. “You have this tension. They don’t really make sense when you put them by themselves, but they also don’t make sense if you leave them entirely with all the other tweets just mixed in.”

Still, if the feeds remain available for public consumption, people will probably find a use for them. They’re still a body of work—some famous users have put more time and words on the platform than they have on paper—and in that equivalent of hundreds of shoe boxes in the attic stuffed with receipts and scraps of unfinished novels, there are windows into artists’ lives and minds. It might not be interpreted as the author intended it to be, but no author can protect their work from future analysis or predict what it’ll come to represent to future generations.

“I think we have always defined literature by how we use it and receive it, rather than the intent, which is ultimately impossible to determine, anyway,” says Gregory Erickson, professor of media and literature at New York University’s Gallatin School of Individualized Study. “Was the Bible intended to be literature? Paul's letters? How about Kafka's writing, which he wanted destroyed? Did Shakespeare think of his plays as ‘literature’?”

As of now, Twitter feeds are just another medium for self-expression. And regardless of any intended purpose for future generations, feeds don’t have to be venerated as a rare cultural relic to still be valuable. They don’t have to reveal secrets that would have otherwise died with their owner. They can be primary sources for research or something fun to look over in the same way people read interviews, book-discussion questions, or to-do lists.

“I remember a friend doing her PhD and going through a writer's archive and finding, written on the back of a takeout menu, a list of magazines in the 1980s that owed him money,” says Emily Schultz, author of The Blondes and founder of the literary magazine Joyland. “To have that kind of everyday detail in a record, we have to start putting Twitter feed or Tumblr posts on microfilm”—or whatever microfilm’s modern counterpart may be.