Executive summary

- Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the United States was experiencing its weakest population growth in a century, a product of record-low fertility and a more restrictive approach to immigration. US annual population growth was running at an annual rate of just 0.5 per cent.

- Australia’s pre-pandemic population growth rate was running around three times faster than the United States at 1.4 per cent.

- Immigration and population growth have historically been a key source of US national power and dynamism and major drivers of innovation and entrepreneurship. But the Trump Administration has embarked on one of the most significant tightenings in immigration policy in US history and used the COVID-19 pandemic to opportunistically accelerate this anti-immigration agenda.

- Yet US public opinion on immigration has become more favourable, not less, over the last 25 years. In the latest polling, for the first time, more Americans want an increase in immigration than a decrease.

- Under a zero net migration scenario, the US population could be expected to peak at 333 million as soon as 2035 and then enter a period of absolute decline to a low of 320 million by 2060.

- In Australia, the October Budget assumes net overseas migration (NOM) is only 154,000 in 2019-20 and -72,000 in 2020-21, and -22,000 in 2021-22, well below the previous peak of nearly 316,000 in the year to December 2008 and the first negative NOM since 1946.

- As a consequence, Australia’s population growth is expected to decrease to 1.2 per cent on an annual basis in 2019-20 and just 0.2 per cent in 2020-21 and 0.4 per cent in 2021-22, the slowest growth since 1916-17.

- Australia will experience a permanent loss of population and productive potential because the government assumes no future make-up of lost NOM, but this is a policy choice that could be offset with a more liberal approach to immigration in the future.

- Restoring and then exceeding pre-pandemic levels of NOM will be essential to economic recovery.

- In the short term, Australia needs to scale up its managed isolation and quarantine capacity to be able to safely process more international arrivals, which are currently capped at 5,575 per week.

- While largely the responsibility of state health authorities, there is a strong case for the federal government to fund a significant scaling up of existing capacity to facilitate a progressive, risk-based reopening of the international borders, while recovering some costs from users.

- The pandemic affords an opportunity to rethink the immigration policy and planning framework. The government’s pre-pandemic reduction in the planning cap on permanent migration from 190,000 per annum to 160,000 should be set aside indefinitely as non-binding in the short run and too restrictive in the long run.

- The National Population and Planning Framework the government released in February contains useful inter-governmental coordination and transparency mechanisms. However, it is a process that risks state government capture of federal immigration policy.

- The government should link immigration and population growth to both pandemic recovery and national security imperatives to increase public support against a backdrop of elevated unemployment.

Introduction

“We lead the world because, unique among nations, we draw our people — our strength — from every country and every corner of the world. And by doing so we continuously renew and enrich our nation. While other countries cling to the stale past, here in America we breathe life into dreams. We create the future, and the world follows us into tomorrow. Thanks to each wave of new arrivals to this land of opportunity, we’re a nation forever young, forever bursting with energy and new ideas, and always on the cutting edge, always leading the world to the next frontier. This quality is vital to our future as a nation. If we ever closed the door to new Americans, our leadership in the world would soon be lost.”

President Ronald Reagan

Final speech as President of the United States, 19 January 19891

“Why are we having all these people from shithole countries come here?”

President Donald Trump

White House meeting with Congressional lawmakers, 13 January 20182

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the United States was experiencing its weakest population growth in a century, a product of a record-low fertility rate and a much more restrictive approach to immigration. US annual population growth was running at an annual rate of just 0.5 per cent in 2019. By contrast, Australia’s population growth rate was running around three times faster at 1.4 per cent for the year ended March 2020.

Immigration and population growth have historically been a key source of US national power and dynamism, as well as major drivers of innovation and entrepreneurship. But the Trump Administration has launched one of the most significant tightenings in immigration policy in US history and used the COVID-19 pandemic to opportunistically accelerate its anti-immigration agenda. Yet, ironically, US public opinion on immigration has become more favourable, not less, over the last 25 years. In the latest polling, for the first time, more Americans want an increase in immigration than a decrease. Seventy-seven per cent of Americans say immigration is ‘a good thing for this country.’3 As with public opinion on international trade in goods and services, there is little evidence for a populist groundswell against immigration, although there is a deep partisan divide between Republican and Democrat voters on the issue.

In Australia, there is also little evidence from opinion polls to suggest that the electorate views immigration per se as a growing problem. Polls by the Scanlon Foundation going back to 2007 consistently find a majority in favour of the proposition that immigration is ‘too low’ or ‘about right,’ with the exception of 2010.4 The lack of a clear trend in the response to this question does not suggest immigration is seen as a growing problem.

To avoid US-style demographic stagnation and a permanent loss of population and productive potential, Australia needs to restart net overseas migration in the short term and change its approach to immigration and population policy in the long term.

Among developed countries, Australia scores just below Canada, Iceland and New Zealand on Gallup’s Global Migrant Acceptance Index.5 An overwhelming 88 per cent of Australians say that their city or area is a good place for migrants to live. Only Canada, New Zealand and Norway report a stronger positive response to this question.6 The response to this question is unchanged since 2010, which is yet again inconsistent with the notion that the electorate perceive immigration per se as a growing problem. Politicians have likely underestimated the electorate’s tolerance for immigration. The public are able to distinguish between immigration as such and the problems caused by an inadequate public policy response to population growth. That said, anti-immigration sentiment is historically correlated with the unemployment rate, so the pandemic downturn can be expected to weigh on pro-immigration sentiment in the short term.7 Historically, negative economic shocks in the United States and Australia have been triggers for major policy changes aimed at restricting immigration.8 However, the pandemic shock may be exceptional in that the collapse in cross-border people flows has dramatised their economic benefits.

With Australia’s international borders largely closed and net overseas migration turning negative, population growth is expected to fall to a rate of just 0.2 per cent in 2020-21 and 0.4 per cent in 2021-22,9 similar to the pre-pandemic population growth rate in the United States. To avoid US-style demographic stagnation and a permanent loss of population and productive potential, Australia needs to restart net overseas migration in the short term and change its approach to immigration and population policy in the long term.

In the short term, Australia needs to scale up its managed isolation and quarantine capacity to be able to safely process more international arrivals, currently capped at just 5,575 a week.10 The government has assumed that this capacity is not scalable, but this is more a self-imposed resourcing constraint rather than a problem with operational or technical feasibility. While largely the responsibility of state health authorities, there is a strong case for the federal government to fund a significant scaling up of managed isolation capacity and quarantine to facilitate a reopening of the international borders while recovering some of these costs from international arrivals. Managed isolation and quarantine capacity should be demand-driven, eliminating the need to ration entry into Australia. Australia should also reopen its border to COVID-free jurisdictions such as Taiwan and the Pacific islands, as it has with New Zealand, regardless of whether these jurisdictions reciprocate.

Restoring pre-pandemic levels of net overseas migration will be essential to economic recovery. The pandemic affords an opportunity to rethink the immigration policy and planning framework the federal government adopted prior to the pandemic. The government’s pre-pandemic reduction in the planning cap on permanent migration from 190,000 per annum to 160,000, reaffirmed in the October 2020 Budget, should be set aside indefinitely. The annual budget planning cap is unlikely to be binding in the short term. It is also too small a permanent migration program in the long term. Australia had net overseas migration around 150,000 in the late 1940s and early 1950s, around 2 per cent of the resident population, with a much smaller housing stock and public infrastructure.11

The National Population and Planning Framework the government released in February contains useful inter-governmental coordination and transparency mechanisms. However, it is a process that risks state government capture of federal immigration policy. State governments find it easier to argue for cuts to immigration than to implement reforms to ease capacity constraints. Australia’s demographic future should not be held hostage by the failings of state and local governments.

Australia is likely to face growing skills shortages amid increased international competition for skilled workers. Like the temporary migration program, the skills-based permanent migration program should be uncapped for those meeting its eligibility criteria, with market-determined wages and labour demand then regulating net migration flows. Given that Australia and the United States are close substitutes for prospective migrants, the inward turn taken by the United States provides Australia with an opportunity to tap the global talent flows that would normally go to the United States. Australia should also aim to capture prospective human and investment capital flight from Hong Kong and pursue greater international labour market integration through its free trade agreement negotiations.

The deterioration in the national security environment associated with the rise of China also makes augmenting Australian national power through population growth a strategic imperative. Australian policymakers should explicitly link immigration and population growth to pandemic recovery and national security imperatives in order to reduce the salience of parochial considerations and local politics in the population debate. The early post-World War II approach provides a model for pro-immigration and population growth narratives that Australian governments could usefully emulate.

Demographic stagnation in the United States

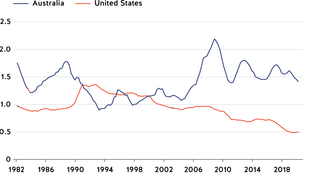

Population is a key element of national power and an underrated source of national security.12 US national power and economic dynamism during the 20th century was built in large part on mass migration during the 19th century. Yet before the onset of the pandemic, the United States was experiencing an unprecedented demographic stagnation, with population growth falling to its lowest level in a century at an annual rate of just 0.5 per cent (Figure 1). Whereas population growth in the first decade of this century averaged close to 1 per cent, in the second decade it has averaged just 0.7 per cent.13

Figure 1. Annual percentage change in the population in the United States and Australia

Figure 2 shows the components of the recent decline in US population growth.

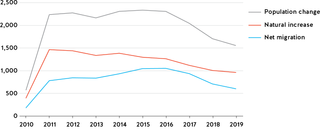

Figure 2. The United States’s population change and components

Change from year earlier, persons, ’000s

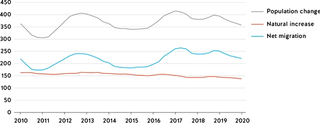

After recovering from a slump due to the global financial crisis in 2008, net migration reached a peak for the current decade in 2016 before declining after the election of President Trump, while natural increase has also been in decline due to record low fertility rates. Natural increase plays a larger role in US population change than in Australia, where net migration dominates natural increase over the same period (Figure 3). Compared to the peak in the 1990s, the contribution of net migration to the growth of the working-age population in the United States fell by 60 per cent between 2010 and 2018.14

Figure 3. Australia’s population change and components

Change from year earlier, persons, ’000s

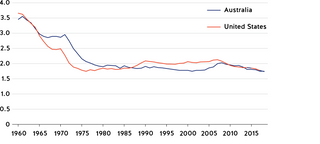

Figure 4 shows the total fertility rate for Australia and the United States. Both are at record lows at around 1.7. Australia’s October 2020 Budget assumes the total fertility rate falls from 1.69 in 2019-20 to 1.58 in 2021-22, with some recuperation to 1.69 by 2023-24.

Figure 4. Total fertility rate in the United States and Australia

In the United States, immigration levels are notionally set by Congress, unlike in Australia, where immigration policy is determined by the executive. But under the Trump Administration, as in other areas of policy, the executive has increasingly usurped the role of Congress. Even before the pandemic, the Trump Administration significantly tightened immigration policy through more than 400 executive orders. The Migration Policy Institute summarises recent developments in US immigration policy as follows:

'Trump’s election brought into mainstream political discourse the previously fringe idea that legal as well as illegal immigration is a threat to the United States’ economy and security...

After pledging to take one of the most activist agendas on immigration in modern times, the administration has delivered on nearly everything the president promised on the campaign trail [in 2016], almost exclusively via executive fiat, ignoring a Congress he had originally pledged to work with on systemic reform. Lawmakers, who remained gridlocked on immigration, sat by as the administration reshaped the system in ways unseen in decades, executing — with methodical detail — a plan to drastically narrow humanitarian benefits, increase enforcement, and decrease legal immigration.

The arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic during Trump’s fourth year in office turbocharged many of these efforts. It gave the administration an opening — in the name of public health and concern for the growing economic crisis — to finish off many of the remaining items on its agenda, including suspending the issuance of visas to certain categories of immigrants and non-immigrants, and effectively ending asylum at the southern border.

Because the Trump administration has pursued these reforms unilaterally, successor administrations could, in theory, undo each change. However, by working at a rapid-fire pace to accomplish more than 400 policy changes on immigration…they may have guaranteed some longevity. It is unlikely that a future administration will have the political will and resources to undo all of these changes at anywhere near a similar pace.’15

The effect of this tightening in immigration policy on migration to the United States has been dramatic. Between FY 2016 and FY 2018, applications for green cards that give foreigners the right to live and work in the United States fell by 17 per cent to their lowest number in half a decade. Temporary visas are also down 17 per cent. Two of the main pathways for entry to the United States are employer-sponsored H-1B visas for skilled workers and F-1 visas for students. President Trump’s Buy American and Hire American executive order in 2017 introduced more restrictive policies for both visa types.16 The executive order explicitly linked a tighter immigration policy to the Trump Administration’s protectionist agenda. Yet the literature shows that previous reductions in the H-1B visa cap lead to the offshoring of jobs with the foreign affiliates of US firms.17

A 22 June 2020 executive ordering barring as many as 200,000 foreign workers and their dependants on non-immigrant H1-B and L-1 visas was notable for its impact on the US companies that rely on the employment of foreign workers. Dany Bahar and his co-authors found that this order lowered the value of US Fortune 500 companies by around 0.5 per cent or US$100 billion. The effect was much more pronounced for firms that had maintained or increased their reliance on foreign workers during the years prior to the order.18 Rather than increasing employment of US workers, the executive order is likely to increase the employment of foreign workers with the overseas affiliates of US firms.

The effect of this tightening in immigration policy on migration to the United States has been dramatic. Between FY 2016 and FY 2018, applications for green cards that give foreigners the right to live and work in the United States fell by 17 per cent to their lowest number in half a decade.

Even before Trump’s executive order, caps on H-1B visas were referred to as ‘America’s national suicide’ because of their role in rationing skilled migration.19 The Trump Administration’s more restrictive policies have seen denial rates increase from 6 per cent in FY 2015 to 21 per cent in FY 2019 for new H-1B petitions for initial employment.20 The rules have since been made even more restrictive.21 The arbitrary quantitative cap on H-1B visas for which demand routinely exceeds supply makes little sense. The requirement that holders of F-1 student visas leave the United States on completing their studies also misses the opportunity to capture and retain this newly acquired human capital within the United States. At the same time, refugee admissions have collapsed to the lowest level since the modern US refugee resettlement program began in 1980. For the FY beginning 1 October 2020, refugee admissions have been reduced to just 15,000, a record low. In previous decades, the United States took as much as half the world’s refugees.22 The overwhelming majority of asylum-seekers are now denied access to the United States.23

During the pandemic, in conjunction with Canada and Mexico, the United States has closed its border to tourists and introduced various ad hoc travel bans and threatened to rescind student visas for those not attending in-person classes, threatening the deportation of as many as one million foreign students. Even without these restrictions, the prevalence of COVID-19 in the United States, along with social and political unrest has made the United States less attractive to prospective foreign students, workers and migrants.

Migration flows have been a powerful engine of US innovation and entrepreneurship. Migrants account for an extraordinary share of both. Inflows of foreign science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) workers explain between 30-50 per cent of aggregate productivity growth in the United States between 1990 and 2010.24 Immigrants to the United States ‘account for 37 per cent of total US innovation, despite only making up 16 per cent of the inventor workforce.’25 One in every 11 new patents in the United States is attributable to a Chinese or Indian migrant in the San Francisco Bay area.26 Migrants account for around 27 per cent of US entrepreneurship.27 Immigration and population growth are also important drivers of new business formation, particularly small business.28

Under a zero net migration scenario, the US population could be expected to peak at 333 million as soon as 2035 and then enter a period of absolute decline to a low of 320 million by 2060.29 While zero net migration is an unlikely prospect, the much more restrictive immigration policy instituted by the Trump Administration will see the United States track closer to this scenario and its demographic peak, while losing many of the benefits of immigration and population growth.

The United States, United Kingdom, Canada and Australia normally receive around 70 per cent of high-skilled migrants to the OECD, with the United States taking close to a half share for the OECD and one-third of high skilled migrants globally.30 With the United States closing its doors and Australia potentially a close substitute for the United States for prospective migrants along many dimensions, a more liberal approach to immigration in Australia could be expected to attract immigrants either rejected or deterred from the United States. As Sherrell argues, ‘the Trump Administration presents the best opportunity we will ever see to present Australia as a place of welcome and innovation, a place where your visa won’t be torn up if you have the “wrong” passport.’31 While the United States has traditionally been the top desired destination for the world’s 158 million potential migrants, Australia ranks equal fourth with France, trailing Canada and Germany (Table 1).32 With the United States tightening immigration policy, Canada is likely to take over from the United States as the main competitor for the top talent Australia seeks. Canada’s permanent migration program for the period 2020-22 aims to admit one million new residents, between 310,000 and 350,000 per year,33 compared to Australia’s program of only 160,000.

Australia is already second only to the United States in attracting migrant inventors34 and has a number of bespoke visa programs designed to attract global talent. But to make the most of the opportunity presented by the United States’s inward turn, Australian needs to liberalise and expand its own migration program.

Table 1. Top desired destinations for potential migrants

|

To which country would you like to move? |

2010-2012 (%) |

2015-2017 (%) |

Estimated number of adults (in millions) |

|

United States |

22 |

21 |

158 |

|

Canada |

6 |

6 |

47 |

|

Germany |

4 |

6 |

42 |

|

France |

5 |

5 |

36 |

|

Australia |

4 |

5 |

36 |

The effect of the pandemic on Australia’s net migration and population growth

Australia enjoyed net overseas migration of 220,500 people in the year ended March 2020.35 Permanent migration in 2019-20 consisted of 140,366 persons, down from 160,323 in 2018-19, with nearly 70 per cent through the skilled migration program.36 Note that some permanent migrants transition from other visa categories and may already be resident in Australia. Temporary migration numbers are uncapped, but the stock of temporary migrants in Australia is typically around 1.6 million. In addition, there are normally around 300,000 people in Australia on visitor visas who mostly do not count as temporary migrants.37 Although temporary migrants are the larger influence on the level of the population in the short term, in the long run, the permanent migration program has the larger influence on population growth as only some temporary migrants transition to permanent migration visas.

Since the mid-2000s, NOM has contributed the majority of Australia’s population growth. Most recently, NOM contributed 61.8 per cent to total population growth of 1.4 per cent for the year to March 2020.38 Australia’s estimated resident population as of the March quarter 2020 was 25.7 million people.

Since then, pandemic-related international border closures have seen net overseas migration collapse. The border is currently closed to all arrivals on visitor and temporary migration visas, while in-bound flights and managed isolation and quarantine have limited capacity for those still able to enter Australia. Thousands of Australians who want to return home are currently unable to do so. Repatriation is thus in competition with immigration for scarce inbound capacity. In addition, Australian citizens and permanent residents are not allowed to depart Australia without authorisation.

Australia will suffer a permanent loss of population and productive potential, because the government also assumes no attempt is made to recoup this lost population growth through future increases in net overseas migration.

In the October 2020 Budget, NOM is assumed to be only 154,000 in 2019-20 and around -72,000 in 2020-21 and -22,000 in 2021-22, the lowest since 1946 and well below the previous peak of nearly 316,000 in the year to December 2008. The pandemic is also expected to have a negative effect on fertility rates. As a consequence, Australia’s population growth is expected to decrease to 1.2 per cent on an annual basis in 2019-20 and just 0.2 per cent in 2020-21 and 0.4 per cent in 2021-22, the slowest growth since 1916-17.39

The government’s October Budget attributes the reduction in population growth ‘mainly…to measures to limit the spread of COVID-19,’40 although weaker economic conditions also play a role. This implies that the reduction in population growth is mostly expected to come from border controls and other public health measures. Australia will suffer a permanent loss of population and productive potential because the government also assumes no attempt is made to recoup this lost population growth through future increases in NOM. But this is an implied policy choice, not just a technical assumption. A more liberal approach to immigration could help Australia to avoid a permanently lower population relative to a ‘no pandemic’ counterfactual.

Australia has seen a robust debate over the growth and level of its population over much of its history.41 However, the pandemic has dramatised the benefits of immigration by forcing an experiment with nearly closed borders. Coupled with domestic lockdowns, this has seen one of the worst economic downturns in our history. To be clear, this is not to argue against these measures, only to highlight their economic effects. Safely reopening the international border should be a much higher priority for government as part of post-pandemic recovery efforts. The government has yet to present a strategy for reopening the border to large-scale international arrivals.

Scaling up managed isolation and quarantine

Inbound migration is currently affected by a combination of international and national border controls, the increased cost and inconvenience of international travel, limited airline, managed isolation and quarantine capacity and airport closures and a global economic downturn reducing labour demand. With the course of the pandemic uncertain both domestically and internationally, it remains unclear how long inbound migration will be affected. However, any significant increase in international arrivals during the pandemic will require a significant scaling up of managed isolation and quarantine. Even with the current border controls in place, demand for travel to Australia exceeds the existing capacity to safely process international arrivals, which is currently capped at 5,575 per week through Sydney, Perth, Brisbane and Adelaide. The current system has insufficient capacity to support a significant reopening of the border. This is assumed to be largely a resourcing problem that can be alleviated through additional public funding and user charges rather than an insurmountable operational problem. While scaling up to pre-pandemic arrival numbers may not be feasible, demand is likely to fall short of these numbers for the near term. Longer term, Australia needs to be able to safely process large-scale international arrivals from the rest of the world or be condemned to being internationally isolated for the remaining duration of the global pandemic.

One option is for the federal government to fund increased capacity to be provided by state governments, while recovering some costs from users. A more graduated, risk-based approach to managing international arrivals would help to limit costs. The government should aim to put in place a demand-driven system that alleviates, if not eliminates, the need to ration international arrivals. As things stand, the government lacks a strategy for safely reopening the international border in a way that would best contribute to pandemic recovery efforts. By way of comparison, the government spent more than $9 billion over four years on the detention and deterrence of asylum-seekers at a cost of $400,000 per person in offshore detention.42 The government has previously shown itself willing to shoulder a substantial fiscal burden to prevent a small number of international arrivals in the name of border integrity. It should be willing to shoulder a similar burden to facilitate the reopening of the borders.

Reconnecting with COVID-free jurisdictions

As other countries are successful in suppressing the virus, Australia should reopen its border with those countries as soon as possible, as it has with New Zealand. It is not necessary for the COVID-free jurisdiction to reciprocate. For example, it would be desirable to open the border to travel from Taiwan and the Pacific Islands, subject to their own outbound border controls. Normal visa conditions specifying the length of stay should be relaxed to reflect return border controls. Allowing all in-bound travel from the Pacific Islands (not just as part of the Pacific Labour Scheme) would serve Australia’s strategic interests by supporting their economic resilience.

Australia should aim to join up with as many countries as possible in a COVID-free travel bubble, although the full benefits of such a bubble will only be realised through the suppression of the pandemic within Australia. The ability to connect with other COVID-free jurisdictions and increase inbound and outbound migration is an important benefit of having suppressed or eliminated the virus domestically.

Post-COVID migration and population policy

Even with a scaled-up system of managed isolation and quarantine, inbound migration and other cross-border people flows are likely to be affected by concerns about the safety of travel, its increased cost and inconvenience, as well as depressed labour market conditions, all of which can be expected to reduce the demand for cross-border migration. In the absence of a vaccine or a moderation in infectiousness and mortality of the virus, depressed migration levels could persist for many years.

The pandemic and its aftermath should prompt a rethink of the government’s Planning for Australia’s Future Population statement from September 2019 and the subsequent National Population and Planning Framework released in February 2020. The framework proposes some useful transparency and inter-governmental coordination mechanisms. Under the framework, the newly established Centre for Population is mandated to prepare a population plan every three years in consultation with state and territory governments, as well as release an annual population statement. While originally a COAG initiative, these measures will continue under the new National Cabinet arrangements.

The pandemic and its aftermath should prompt a rethink of the government’s Planning for Australia’s Future Population statement from September 2019 and the subsequent National Population and Planning Framework released in February 2020.

The Framework was developed to facilitate ‘managing and planning for population changes’ on the assumption that ‘better population planning will help overcome capacity constraints in Australia’s biggest cities.’43 This objective will only be achieved if the planning process focuses on easing capacity constraints to accommodate long-term growth in immigration and population. The risk in such a process is that it might seem easier to politicians to trim population growth to fit these constraints than it is to alleviate them. The process could become a vehicle for reform-resistant state governments to reduce inward migration rather than opening up, effectively fitting migration to supply-side policy failures in areas such as housing and infrastructure. Land use and zoning restrictions have been particularly resistant to reform and are the fundamental cause of problems with housing affordability. Governments are also averse to introducing congestion charges that could alleviate infrastructure constraints.44

The National Population Planning Framework should be used as a lever to increase pressure on the states to reform. Instead, it risks becoming a process through which the states capture federal immigration policy and co-opt it to a parochial political agenda. For example, the NSW Government used the former COAG process to argue for immigration to NSW to be more than halved, from 100,000 to 45,000. NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian has hailed the new ‘bottom-up’ planning process as ‘a huge victory.’45

In line with the 2019-20 Budget announcement, the Planning for Australia’s Future Population Statement reduced the planning cap for the permanent migration program from 190,000 to 160,000, reducing permanent migration visas by 120,000 over the forward estimates. This reduction was made even before the Framework was established. The cap was reaffirmed to the October 2020 Budget, although the number of Family Stream Places within the cap has been increased from 47,732 to 77,300 on a one-off basis for 2020-21, presumably reflecting an expectation that skilled migration will be weaker. The refugee intake will be reduced from 18,750 to just 13,750 over the next four years.46 In the wake of the pandemic, the planning cap on permanent migration of 160,000 is unlikely to be binding given expected net migration numbers. Even before the pandemic, permanent migration numbers would sometimes fall short of the federal budget’s planning cap, as was the case in 2019-20. The planning cap should be set aside. Immigration policy should instead focus on rebuilding NOM and then making up for lost inbound migration during the pandemic to avoid a permanent loss of population and productive potential.

The aftermath of the pandemic affords an opportunity to experiment with uncapping the permanent skilled and family-based migration programs to support the recovery in NOM. The skilled occupations list and other criteria for permanent migration visas could be maintained, but without quantitative limits on visa numbers. Qualitative criteria could also be relaxed while NOM is below pre-pandemic levels. The current skills classifications need to be updated and broadened in any event.

The aftermath of the pandemic affords an opportunity to experiment with uncapping the permanent skilled and family-based migration programs to support the recovery in net overseas migration.

The skills-based permanent migration program has been used by the government to micro-manage labour market imbalances. In the long run, the government should allow the size of the permanent migration program to self-regulate based on current and prospective labour demand and the level of wages in the targeted skill and occupational categories. Rising wages due to shortages in segments of the labour market will attract, while falling wages reflecting excess supply will deter prospective immigrants, although the absolute level of wages relative to overseas may dominate wages growth in attracting prospective migrants. The market is more likely to send the right signals about prospective shortages or a surplus of skilled workers. The temporary migration program already operates on this basis, albeit with a floor on wage rates. Qualitative criteria would still serve to limit overall migrant numbers, but without arbitrary caps.

Following recovery from the pandemic, Australia is likely to face skills shortages amid growing international competition for skilled workers. Pre-pandemic, additional labour demand through to 2024 was projected at 4.1 million job openings, with more than half resulting from replacement demand as Baby Boomers exit the labour force and with a growing skew to skilled occupations.47 The pandemic downturn will likely reduce this demand, but labour supply will still struggle to keep pace without a significant contribution from migration.

Experience with Australia’s uncapped Temporary Work Skilled Visa program shows that skilled migration increases the wages of native workers and induces native workers to specialise in occupations with a high intensity of communication and cognitive skills. Uptake of the visas correlates with economic activity, with visa numbers self-regulating based on economic conditions. It should be noted that firms are required to pay foreign workers a minimum salary equal to at least that of comparable native workers.48

Since the mid-1990s, Australia’s permanent migration program has been weighted more heavily to skills-based than family migration. Uncapping the permanent migration program could see this balance shift back towards family migration, although eligibility criteria would still serve to limit overall numbers. However, migration policy has likely over-weighted human capital over family and social networks in predicting migrant success. At least one study comparing the experience of Asian migrants to Australia and the United States suggests that migration outcomes in the United States are better than in Australia despite, or possibly because, of the greater weight on family migration in the United States relative to Australia.49

The 2019-20 Budget and the Planning for Australia’s Future Population Statement also sought to divert 23,000 of the planned 160,000 places in the permanent migration program to regions, defined as ex-Sydney-Melbourne-Perth-Brisbane-Gold Coast.50 The stated rationale was to ‘take pressure off the big capitals,’ which were said to suffer because ‘freeways have slowed, trains are sometimes at crush capacity and housing construction has not always kept pace.’51 But these shortfalls are domestic policy and planning failures. Curbing migration just makes these failures even more costly.

Diverting migrants to the regions will only make them less productive. Migrants typically enjoy higher wage rates, reflecting higher productivity,52 than natives, but this higher productivity depends on migrants being able to access the higher paying jobs that are typically found in big cities. The ‘place premium’ that applies to cross-border migration likely applies to a lesser degree to internal migration.53 Migrants are attracted to big cities for the same reasons as natives. People are more productive and better compensated in big cities due to agglomeration effects. Talent tends to cluster in cities where migrants can take advantage of proximity to those with complementary skills. My previous United State Studies Centre report, Globalisation and labour productivity in the OECD: What are the implications for post-pandemic recovery?, shows how openness, including to cross-border people flows, is an important driver of the level of productivity in the long run.

Globalisation and labour productivity in the OECD: What are the implications for post-pandemic recovery and resilience?

Diverting migrants to the regions and smaller cities holds the migration program hostage to a misdirected regionalism and regional politics that is bad for national productivity growth. There are also questions about how the government can enforce the diversion of migrants to the regions given the pull of the big cities. It is likely that internal migration is already distorted by housing supply and infrastructure failures pushing people out of cities. Mandating immigration to the regions will at best induce substitution with internal migrants if nothing is done to alleviate these capacity constraints in big cities.

Congestion and pecuniary externalities like higher house prices are partly a reflection of agglomeration effects. In net terms, it is likely there are positive externalities from increased urban density. Australia’s cities are, if anything, lacking in population density. Sydney is the 99th largest urban area in the world by population but 46th in terms of land area. That puts Sydney 934th in terms of population density, in between those other heaving metropolises of Cuiaba in Brazil (933rd) and Krasnoyarsk in Russia (935th). Melbourne is 101st by population, 34th by land area, but only 968th by population density, equal with Quebec in Canada.54 This lack of density reflects maximum density caps and other restrictions on new residential developments, such as building height restrictions.55 Housing supply needs to be liberated to accommodate a larger migration program and to improve housing affordability for natives. Trimming migration to fit a housing stock that is being artificially restricted by state and local governments holds Australia’s future economic development hostage to parochial politics.

The economics of population, productivity and living standards

The long-run relationship between population and real GDP per capita is viewed somewhat ambiguously by economic historians and economists. There is little argument that population growth and net migration have contributed to ‘extensive’ economic growth, that is, in the size of the economy. There is less agreement on their contribution to ‘intensive’ growth, that is, growth in real national income per capita, a widely used proxy for average living standards.

Economists have generally approached this question in a growth accounting framework based on standard neoclassical growth models and assumptions. The contribution population makes to real output in these models is via the size of the labour force and hours worked, augmented by technology and human and physical capital. Improvements in productivity are the main driver of economic growth and average living standards in the long run.56

Neoclassical growth models with constant returns to scale imply that growth in labour inputs yields only transitory effects on the level of output and is thus broadly neutral for long-run growth in output per worker. However, population growth can also subtract from economic growth and living standards to the extent that it leads to a reduction in capital per worker and thus lower productivity.57 There is no necessary connection between population and capital accumulation or technology in these models. The empirical cross-country growth regression literature exemplified by Mankiw, Romer and Weil has typically found negative, though modest, effects on the level and growth rate of national income from population growth, usually mediated through the steady-state capital-labour ratio and/or changes in labour force participation rates.58

Population may be endogenous to real GDP per capita. The level of real GDP per capita is an important determinant of trends in fertility and mortality rates, as well as a driver of net migration.59 Endogenous growth theory implies that population growth may also drive technical change, although this literature is divided on whether the relationship between population and productivity is positive or negative. Jones maintains that US and world growth is driven by research effort that is proportional to population.60 Romer shows that ‘an increase in the labour force can reduce the rate of technological change’ because labour scarcity drives innovation.61 The implications of Romer’s model find historical support in Habakkuk’s study of the United States and the United Kingdom in the 19th century.62

Another stream in the endogenous growth tradition maintains that population growth results in more generalised non-labour scarcities and short-run pecuniary externalities that in turn drive long-run technical change. In this tradition, the transmission mechanism from population growth to technical change is much broader and more mundane than the research and development (R&D) and human capital accumulation channels that have been the usual focus of the endogenous growth literature. The contribution of population growth to knowledge growth is difficult to measure and model and has traditionally been neglected in favour of more tractable models and relationships. Simon,63 Simon and Kuran,64 Kuznets65 and Boserup66 have nonetheless shown a positive long-run relationship between population growth, population density, innovation and technological change. This perspective is related to the observation that real commodity prices tend to decline in the long run.67 This stream of endogenous growth theory suggests the possibility of a positive long-run relationship between population and the level of real GDP per capita that is at odds with the implications of standard neoclassical growth models and the empirical cross-country growth regression literature.

Students of Australian economic history have for the most part neglected the long-run relationship between population and the level of per capita income. Most of the interest in demography on the part of economic historians has been confined to the implications of immigration and the age structure of the population for the business cycle and the expenditure composition of economic growth rather than the determination of per capita income over time.68 Pope is notable in examining the relationship between population growth and per capita income for the period 1900-30.69 Adopting standard neoclassical assumptions, Pope argued that since growth in net migration exceeded capital accumulation, immigration had likely lowered Australia’s stock of capital per worker and thus productivity, increasing real GDP, but lowering real GDP per capita. Pope blamed Australia’s historically poor per capita economic growth on immigration, arguing that Australia traded-off living standards against a bigger population to satisfy the ‘populate or perish’ imperative.

This view has support from other economic historians. Kuznets, although sympathetic to the view that population growth has positive implications for long-run improvements in living standards, also thought that a low capital-labour ratio was implicated in Australia’s relatively low per capita GDP growth between the 1860s and the early post-World War II period.70 Gruen’s 1986 Shann Memorial Lecture maintained that ‘our high population growth rate...has exercised a negative effect on the improvement in our average living standards.’71 Jolley reached a similar conclusion in relation to immigration.72

The implications of population growth and net migration for per capita income has often been considered in the context of contemporary policy debates, particularly in relation to the economic implications of population ageing. While not strictly historical in focus, this modelling is often informed by historical data and calibrated on the basis of historical relationships. In contrast to demographers like McDonald,73 Guest and McDonald argue that a decrease in fertility could lead to a modest improvement in future living standards in Australia.74 Their conclusions are specific to their simulation model, which adopts standard neoclassical assumptions, including constant returns to scale and exogenous technology. The modest improvement in living standards arises from the reduction in investment needed to maintain the capital-labour ratio and the simulation’s implication that future increases in taxes due to an ageing population will have only a very small negative impact on future labour supply.

McDonald and Temple present ‘a partial analysis of the impact of migration on Australia.’75 The results are obtained by running the federal Treasury’s Intergenerational Report (IGR) demographic projections through the Productivity Commission’s demographic model. While not an economic model, their conclusions are consistent with standard models and the Treasury’s IGR projections in arguing that ‘the impacts of migration upon the rate of growth of GDP per capita derive from the impact of migration upon the proportion of the population that are in the labour force which, in turn, is determined largely by the extent of population ageing.’ Immigration boosts real GDP per capita, but only by increasing hours worked due to a slowing in population ageing. This conclusion is characteristic of models that limit the contribution of population growth and immigration to real GDP per capita to the direct contribution made by labour inputs. Although immigration is widely thought to have had little or no impact on the age structure of the population historically, McDonald and Temple argue it may have some impact in the future.

The Productivity Commission’s 2006 report Economic Impacts of Migration and Population Growth concluded that ‘migration has relatively small but generally benign economic effects.’ The report modelled an increase in skilled migration of 50 per cent (an additional 39,000 migrants each year for 20 years), which raised the population level by 3.3 per cent, with real GDP per person rising 0.71 per cent. The modelling for the Commission also assumed that immigration subtracts from labour productivity due to a decrease in the capital-labour ratio. As the Commission readily concedes, it is inherently difficult to quantify and model factors such as the gains from trade and increased competition, much less the role of innovation, so these considerations are omitted from the modelling. The Commission’s 2006 modelling and conclusions do not differ substantially from the major Australian studies into the economic implications of immigration conducted in the 1970s and 1980s, including economic modelling for the 1988 Fitzgerald Committee of inquiry, which concluded that ‘the positive effects of immigration on the economy are necessarily limited. They can account for only a fraction of total economic growth.’76

More recently, in its 2016 report on the Migrant Intake into Australia, the Productivity Commission modelled a number of net migration scenarios relative to a business-as-usual scenario in which NOM was held at its long-run historical average of 0.6 per cent of the population. Projected through to 2060, a zero NOM scenario yielded a 7 per cent decline in real GDP per capita, whereas a 1 per cent NOM scenario yielded an increase of 3 per cent, a 10 percentage point differential in living standards by the end of the projection period.

A common theme running through this literature is the very restricted role given to population and net migration in driving growth in real GDP and real GDP per capita. This role is usually confined to the direct contribution of labour inputs and the role of the capital-labour ratio in driving productivity. There are some exceptions to this approach found in the literature. Nevile argued that population growth leads to improved productivity growth through the ‘Salter effect,’ named after the work of Australian economist Wilfred Salter.77 In contrast to Romer, Salter maintained that faster population growth gives rise to a more modern and productive capital stock. Nevile’s approach is otherwise conventional in maintaining that the Salter effect must compete with the role of immigration in diluting the capital-labour ratio and productivity.

Overall, the conclusions reached by economists in the neoclassical tradition about the contribution of population growth to growth in living standards reflect the trivial way in which population enters the neoclassical growth framework. The endogenous growth literature provides a much richer basis for considering the economic benefits of population growth, not least because it takes the roles of innovation and entrepreneurship seriously.

Capturing human capital flight from Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

China’s increasingly repressive policies towards the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) are likely to see increased outward migration from Hong Kong on the part of its expatriate population and those Hong Kongers with international migration rights such as UK passport holders. Foreign firms are also likely to reconsider HKSAR as a location for regional operations. The Australian government has already relaxed visa arrangements for Hong Kong and is seeking to attract some of the 1,000 international companies that have their regional headquarters based there and might consider relocating to Australia.78 However, the new visa arrangements are mainly focused on temporary migration. Uncapping the permanent migration program could be expected to increase the number of permanent visa pathways. The Australian government should also follow the United Kingdom’s lead in providing a permanent visa pathway to British National (Overseas) citizens ordinarily resident in Hong Kong to move to Australia.

CANZUK free migration area

Pandemic border closures notwithstanding, Australia and New Zealand already enjoy largely free cross-border migration and a high degree of labour market integration. Migration flows between Australia and New Zealand are self-regulating based on relative economic conditions in the two economies. An obvious question to ask is whether public policy should aim to extend this free migration zone to other countries with a view to capturing the benefits of greater labour market integration. One proposal is to create a free migration zone taking in Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom (CANZUK), possibly as part of a free trade zone.79 In principle, such an agreement could also be extended to the United States. Given the common language and cultural affinity between these countries and similar occupational and other standards, there is considerable scope for cross-border labour market integration between these economies.

Pro-natalist policies

Population growth is also a function of natural increase, the net of births and deaths. As with other advanced, high-income economies, Australia’s fertility rate has been on a declining trend and is currently around 1.74 babies per woman,80 slightly above the United States rate of 1.71, which is a record low for the United States.81 The Australian government’s October 2020 Budget assumes a decline in fertility to 1.58 in 2021-22. Economic downturns typically have a negative effect on fertility. Australia’s fertility rate last peaked in 2008 before the onset of the global financial crisis, coincident with the peak in net migration, contributing to strong population growth in that year. The COVID-19 pandemic is also assumed to lower fertility, at least temporarily, although with the expectation of some recuperation post-pandemic.82

Australia’s realised fertility rates are below the stated preferences of Australians for around 2.5 children, as well as self-reported expected fertility rates, pointing to the possibility of a ‘baby gap.’83 But based on international evidence on the responsiveness of fertility to government benefits, the budget cost of an additional baby was estimated in 2008 at around $300,000.84 Immigration, particularly skilled migration, is economically more cost-effective than pro-natalist policies in boosting population growth. However, policies designed to reduce the cost of living can be expected to lower barriers to family formation and fertility, without a direct cost to the government. For example, improving housing affordability by increasing housing supply, as already recommended in this report, could be expected to lower a significant obstacle to both preferred and realised family size at no direct cost to the budget.

Immigration and national security

As already noted, population is a key element of national power, determining the size of the economy and the ability to resource a defence force and foreign diplomatic presence. It is widely accepted that Australia’s strategic environment has deteriorated in the last decade, yet this growing sense of insecurity has not been matched by a desire on the part of policymakers to augment Australia’s strategic weight through immigration and population growth. The government is assuming that Australia will be a permanently smaller country due to the pandemic, but this is partly a policy choice about the future level of immigration and not just the effects of the pandemic.

Demographic stagnation in the United States is a threat to Australian national security by reducing the national power of Australia’s most important alliance partner. As Andrew Carr has argued, ‘we can no longer have two separate conversations about population size and a dramatically worsening security environment. These issues need to be relinked.’85 Making the connection to national security and post-pandemic recovery imperatives will help politicians make the case for more immigration at a time when the unemployment rate is likely to remain elevated. This was an important element in how the government sold the benefits of immigration to Australians in the early post-World War II period when Australia sustained net overseas migration at an annual rate of around 150,000. Significantly, the post-war period was also one characterised by record growth in the housing stock.86

Conclusion

Even before the pandemic, the United States was suffering major demographic stagnation, with a population growth rate at century lows. President Trump’s draconian tightening of immigration policy has seen net migration to the United States fall to the lowest level in a decade. Immigration has long been a key source of US national strength and dynamism. In particular, it has been a major driver of US innovation, technological leadership, new business formation and entrepreneurship. Demographic stagnation now threatens the future power and prestige of the United States. Without significant net migration, the US population will go into outright decline as soon as 2035. The changes the Trump Administration has wrought to the US immigration system are unlikely to be significantly unwound by a new US administration, if only due to political inertia.

Matt Yglesias, in his recent book One Billion Americans: The Case for Thinking Bigger, reaches conclusions about the United States that are arguably also applicable to Australia:

Letting more hardworking and talented foreign-born people move here is not hard. On the contrary, it’s keeping people out that’s hard. Providing financial support so that Americans can have as many children as they say they’d like to is a big change, but there’s nothing particularly difficult about it. Letting builders make whatever kind of housing their customers want to buy is easy. Shifting economic activity to places where land and buildings are cheap is a little more difficult, but it’s hardly a voyage to the moon. Copying a traffic-management paradigm that Singapore implemented in the mid-’70s isn’t hard at all, nor is copying long-standing German commuter-rail practices. These easy things feel hard only because we’ve become accustomed to a political culture that can barely do anything at all.87

In contrast to the United States, Australia has maintained its demographic dynamism, at least prior to the pandemic, with a population growth rate around three times faster than the United States. The collapse in net overseas migration as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic affords an opportunity to rethink migration and population policy. The federal government has launched a number of bespoke visa programs to attract global talent, but the migration program should also aim to boost overall migrant numbers to recoup pandemic losses and avoid a reduction in Australia’s long-run productive potential.

Prior to the pandemic, the government sought to trim the permanent migration program and put in place a population planning process that risked state government capture of federal immigration policy. Some state governments find it easier to argue for cuts in migration than to champion the reforms needed to increase the capacity to accommodate increased migrant inflows. Instead, the population planning process should be used to leverage greater reform efforts from the states.

Some state governments find it easier to argue for cuts in migration than to champion the reforms needed to increase the capacity to accommodate increased migrant inflows. Instead, the population planning process should be used to leverage greater reform efforts from the states.

An immediate priority is to scale up existing managed isolation and quarantine capacity to facilitate an increased number of international arrivals. The current limited capacity is a function of limited resourcing rather than operational feasibility or public health requirements. A risk-based approach to processing international arrivals should facilitate this scaling up. The government should also reopen the borders to COVID-free jurisdictions like Taiwan and the Pacific Islands, as it has with New Zealand.

Longer term, the federal government should use the post-pandemic recovery period to experiment with uncapping the permanent migration program. The skills-based program can be run on a similar basis to the temporary migration program, with labour market conditions and qualitative selection criteria largely regulating migration flows. The family program could also be uncapped subject to existing eligibility criteria. The migration program should aim to capture migration flows that might otherwise be deterred from the United States, as well as capturing prospective human capital flight from Hong Kong.

Australia’s free trade agreement negotiations should also aim to liberalise the cross-border flow of labour, with a focus on creating a Canada-Australia-New Zealand-United Kingdom free migration zone. Greater labour mobility will complement the increased trade and investment flows sought through these agreements.

Selling the benefits of immigration and population growth to the electorate will be made easier if the government connects the benefits of population growth to national security imperatives arising from Australia’s deteriorating strategic environment. Liberating housing supply from existing constraints would improve housing affordability for immigrants and natives alike. The early post-World War II period, when Australia enjoyed net migration rates around 150,000 annually, provides a model in which population growth was linked to economic reconstruction and national security concerns, while Australia’s governments facilitated record growth in the housing stock to accommodate a growing population. Higher rates of unemployment will make this narrative a harder sell in the short run but should be easier for governments to promote as labour market conditions improve and skills shortages become evident.