Flipping the switch on far-UVC

We’ve known about far-UVC’s promise for a decade. Why isn't it everywhere?

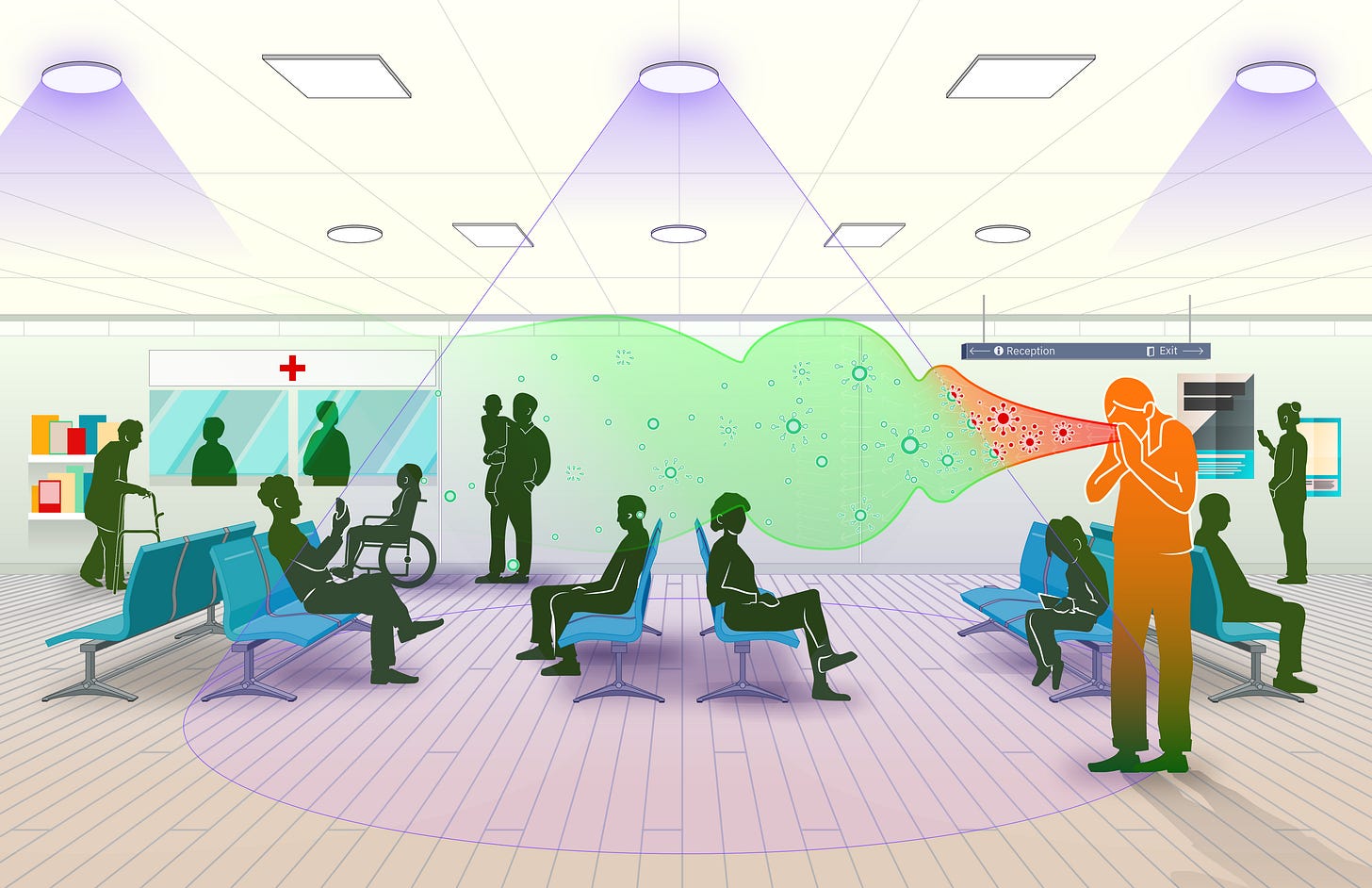

For all of the progress that humanity has made against water-borne, food-borne, and vector-borne disease, we remain devastatingly vulnerable to germs that spread through the air.

One of the best shots we have at turning the page on airborne disease is an emerging type of germicidal UV (GUV) light called far-UVC. Over the last decade, researchers have documented its ability to eliminate pathogens while being safe for humans. A landmark study from 2022 found that far-UVC reduced the concentrations of airborne bacteria by 98.4 percent in a room-sized chamber, all while operating within safe UV exposure limits. Compared to standard ventilation, this was the equivalent of changing the air completely over in the room 184 times every hour. To put that in perspective, the CDC recommends 5 or more air changes per hour in the workplace. Even hospital operating rooms in the US only require 20. Far-UVC is effective against viruses too; airborne coronaviruses are more susceptible to far-UVC than the same bacteria used in the other study.

Writing for Works in Progress two years ago, I called far-UVC ‘the most promising new candidate for building a pandemic firewall.’ Since then at the nonprofit where I work, Blueprint Biosecurity, we’ve spent thousands of hours poring over the academic literature. We’ve spoken to hundreds of experts in photobiology, atmospheric chemistry, indoor air quality, building science, environmental engineering, epidemiology, public health, and many other disciplines. With the benefit of all that further investigation, I still stand by that original claim today.

Considering the impressive findings quoted above, as well as society’s urgent need for better defenses against airborne pathogens, you might expect there to be a booming market for far-UVC devices. But most people have still never heard of it, let alone considered using it. What could explain this?

While we have promising lab studies, far-UVC researchers have not yet produced the kind of compelling real-world data that is needed to support safety and efficacy. If far-UVC were a drug, the situation would be straightforward: it would not yet be approved by the FDA, and would need to go through clinical trials before anyone could even buy a lamp.

But there is no FDA that needs to approve of installing a far-UVC lamp in an office, school, or nightclub. This is a double-edged sword. Lamps are freely available for purchase, but the flipside of there being no regulator is that there is also no entity to confer public trust in the safety and efficacy of the technology.

Nor is there a corporation willing to make an upfront investment in expensive clinical research when other far-UVC manufacturers will be able to free ride off a successful outcome. No for-profit entity can afford to obtain the standard of evidence expected by risk-averse institutions who are in a position to confer public trust.

The absence of a coordinator between research, industry, and these institutions is also a hindrance to progress. Instead of the select amount of ongoing far-UVC research being purposefully directed towards a common goal, it takes place in academic silos.

Herein lies the challenge and opportunity for catalyzing the development of far-UVC. There is no clear precedent for a technology like far-UVC gaining the trust of the public. This is the problem we set out to solve.

Over the past two years, Blueprint Biosecurity has been hard at work creating a plan. We’ve captured it in a report that we call our far-UVC Blueprint. Today, March 10th 2025, it’s being released to the public in preprint form.

In addition to detailing what we know about how, and how well, far-UVC works, the report identifies a handful of critical research questions that must be answered to enable trusted institutions to confidently endorse far-UVC. It starts with activities analogous to the goals of FDA Phase I and II trials: quantifying the doses of far-UVC needed in real applications and making sure our understanding of its biological and chemical effects is complete. After that comes Phase III: cluster-randomized controlled trials to obtain high quality evidence of far-UVC’s real world effectiveness.

As we publish the preprint, there are three things we’re launching today to move our work on this forward.

For the next month, we’re actively soliciting public feedback on our plan and looking to grow our pool of external reviewers we use to sharpen our work before public release. Find out more here.

We’re growing our far-UVC team. We’ve just posted a job listing for a central role in managing our forthcoming far-UVC field building work. Apply here.

Finally, we’ve launched a new Substack we’re calling Far-UVC Field Notes. Each issue will document the progress of far-UVC and our work on it. Read more about it and subscribe here.