The International Monetary Fund (IMF), like their counterparts at the OECD, tend to be big fans of immigration. And if some is good, more is generally better. If immigration in some times or places make a lot of sense, it probably should do so in all times and places. Or at least that is the sort of tone that often pervades their documents. There is, no doubt, a variety of reasons for these stances – some good, some less so – but it can’t hurt that these organisations are made up largely of highly-paid economists who have themselves left their own countries to ply their trade in some of the richer and more comfortable capitals of the world. Theirs is, typically, a migrant’s perspective, rather than that of a citizen of a recipient country. And no one doubts that migration typically, or an average, benefits the migrant. If it didn’t, then mostly they wouldn’t move.

Last year, the IMF was out championing the potential gains from immigration in one of their flagship publications, the World Economic Outlook. I wrote here about the work they were highlighting – some empirical estimates suggesting some rather implausible things.

If this model was truly well-specified and catching something structural it seems to be saying that if 20 per cent of France’s population moved to Britain and 20 per cent of Britain’s population moved to France (which would give both countries migrant population shares similar to Australia’s), real GDP per capita in both countries would rise by around 40 per cent in the long term. Denmark and Finland could close most of the GDP per capita gap to oil-rich Norway simply by making the same sort of swap. It simply doesn’t ring true – and these for hypothetical migrations involving populations that are more educated, and more attuned to market economies and their institutions, than the typical migrant to advanced countries.

Come to think of it, the model also implies that if 20 per cent of New Zealanders moved to Australia (oh, they already have) and an equivalent number of Australians moved to New Zealand, we could soon be as wealthy as Australia is now, simply by exchanging populations. Believe that, as they say, and you’ll believe anything. (Since the New Zealand Initiative also drew on this IMF work in their advocacy piece on New Zealand’s immigration policy, I also touched on the Fund research here.)

Last week, the IMF released their Article IV report on New Zealand. In the main text, there is a pretty typical, but not very specific, tone around the generally beneficial effects of high rates of immigration to New Zealand. The Fund’s Board happily went along, noting among other things.

Directors agreed that measures to lift potential growth should focus on leveraging the benefits from high net migration and interconnectedness.

As I noted last week, there was no hint of what these benefits might be, or how they might be “leveraged”.

But buried deep in the package of papers released with the Article IV report was an annex with some interesting empirical research on the economic effects of immigration. It can be found starting on page 39 of the report document. These annexes, or what used to be called “selected issues” papers, involve someone on the Fund staff team doing some more in-depth work on a topic of relevance to the specific member country. Topics are usually agreed with, and may be suggested by, the national authorities (in practice, the Reserve Bank and Treasury). I commend those agencies for asking for, or agreeing to, this work.

In opening, the paper notes

Over 1990-2014, net migration measured as annual net flow of foreign born

population averaged about 0.9 percent of previous-year population, which is around twice the OECD average

and

In New Zealand both inflows and outflows fluctuate markedly over time, which has a resulted in more volatile net migration compared to most other OECD countries.

The IMF’s own starting presumptions are clear.

The educational attainments of New Zealand’s migrant population suggest that

migration policy has contributed to raising human capital

They include a chart showing that, relative to other OECD countries, a larger proportion of New Zealand’s migrant have a university degree, but appear unaware of the OECD skills data that shows that, even so, the average skill level of immigrants has still been lower than the average skill level of natives.

But the focus of the paper is on two quite separate pieces of empirical analysis, one focused specifically on cyclical effects in New Zealand, and the other focused on longer-term growth and productivity effects, but not specific to New Zealand at all.

The modelling of the cyclical effects appears to be very similar to some research work published by the Reserve Bank a year or so ago (the paper is here, and my discussion of it is included in this post), which distinguished between net migration flows between New Zealand and Australia, which are heavily influenced by what is going on in the Australian labour market, and other net migration flows.

For the “other” migration they find exactly the sorts of results one would expect, and which researchers in New Zealand have pretty much always found (going back many decades). For these migration shocks, the demand effects tend to outweigh the supply effects in the short to medium term, This is a point that seems to be repeatedly lost in the current popular debate on immigration. Migrants aren’t just workers, they are consumers (and need new capital stock). So in the short to medium term immigration shocks tend to lower unemployment (and increase the “output gap”). All else equal, in the short to medium term, they increase inflation pressures.

Both the IMF and the Reserve Bank’s researchers find something a bit different for migration between New Zealand and Australia that is associated with Australian labour market shocks (proxied by changes in Australian unemployment). Reduced net flows to Australia are associated with slightly higher unemployment (and lower employment) in the short-term – and, thus, presumably weaker inflation pressures.

Unfortunately (and perhaps they were pressed for space), the IMF left out the critical point that the Reserve Bank’s researchers had acknowledged

the Australian unemployment shock could capture other indirect demand effects. There are common drivers of labour market movements in Australia and New Zealand, and these common drivers mean that the Australian and New Zealand unemployment rates typically co-move. A high Australian unemployment rate is reflected in higher unemployment in New Zealand, but also high net immigration.

In other words:

- similar international shocks often hit both New Zealand and Australia. When they do, Australian unemployment rises, and (net) fewer New Zealanders go to Australia, but New Zealand unemployment also rises, not because of the change in the immigration numbers but because of the international adverse shock itself.

- Australia is also the largest trade and investment partner for the New Zealand economy. Thus, any downturn in Australia (whether home-sourced or global) will reduce demand for New Zealand goods and services, and perhaps investment in New Zealand by the many Australian companies operating here. All else equal, those effects will weaken demand and employment, and raise unemployment, in New Zealand. At the same time, (net) fewer New Zealanders will be moving to Australia. The estimates in the Reserve Bank and IMF models capture the combined effects of all this, not just the effects of a change in immigration flows between New Zealand and Australia.

On my reading, the safest conclusion remains – as it always has – that increased net migration inflows (especially if they arise from things exogenous to the New Zealand market – whether global events or New Zealand policy changes) increase pressure on local resources in the short to medium term. But if, at the same time, demand in one of our major markets is also weak, the overall effect (of the weak international demand and the increased immigration) will not necessarily be to require higher interest rates. If we could have one without the other, there would be a cleaner test. With the Australian flows, no one has yet done the research to enable us to do so.

The second half of the IMF paper looks at “how migration affects growth, factor accumulation, and productivity in a sample of OECD countries”. This is similar to what the IMF did in the paper they published last October (see above), and relative to that paper it has some pros and cons.

The downside is that it uses a smaller sample of OECD countries (this time only 14, whereas the earlier paper used 19). And whereas in the earlier paper, all the countries were already advanced market economies in 1990 (when the data start), this one includes Hungary. Unlike the earlier paper, this paper also includes Luxembourg, which complicates things because a large proportion of Luxembourg’s workforce doesn’t actually live in Luxembourg, so making sense of their data is harder than usual (there is, for example, a very large gap between GDP – stuff produced in the country – and GNI – income accruing to residents of the country).

On the other hand, the earlier paper only looked at GDP per capita, and simply hand-waved about where the large suggested gains from migration might be coming from, suggesting that we might expect to find a boost to total factor productivity (TFP) growth. By contrast, in this exercise for the New Zealand Article IV the Fund’s researchers look specifically at productivity measures, both labour productivity and estimates of TFP.

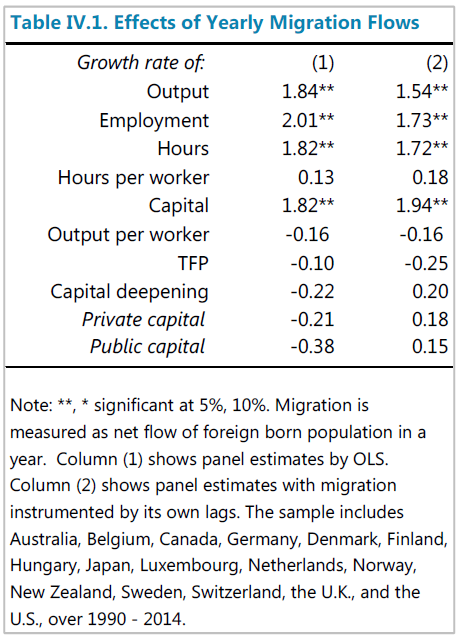

The modelling exercise does not produce results for any individual country; rather they are average results across this pool of very different countries. Here is the summary table from the IMF’s paper

Tables like that can be a bit hard to read. On GDP per capita, the results suggest that over this period and for these countries on average

“a net migration flow of 1 per cent of total population is associated with an increase in output of nearly 1.5 – 2 per cent, driven by an increase in both employment and the capital stock”

That sounds good (and, if still implausibly large, not inconsistent with the results in the earlier IMF paper). But note that there was no mention of productivity gains in that quote. We’ve seen these sorts of results, in different types of models, in Australasia before. Since migrants tend to be relatively young they, for example, tend to have a higher average labour force participation rate than natives (not too many 80 year migrants). One can get a boost to GDP per capita, at least for a time, even if there are no gains in productivity, and if there are no gains in productivity there are no long-term gains to natives. This was the sort of result the Australian Productivity Commission suggested in its recent report on immigration.

So what did this particular IMF cross-country empirical exercise suggest about productivity effects?

For labour productivity, you can compare the two lines ‘output” and “hours”. On one specification, output and hours increased almost identically (so no labour productivity effects at all, and in the second specification of the model, output increases less than hours (1.54 vs 1.72). We don’t know if that difference is statistically significant, but lets assume not. At best, immigration produced no gains to labour productivity, across these particular 14 countries, in the last 25 years.

And what of TFP? The authors report those results directly. In both specifications, the coefficients are negative, but not statistically significant. Again, at best, no TFP gains from immigration across this pool of countries over the last 25 years.

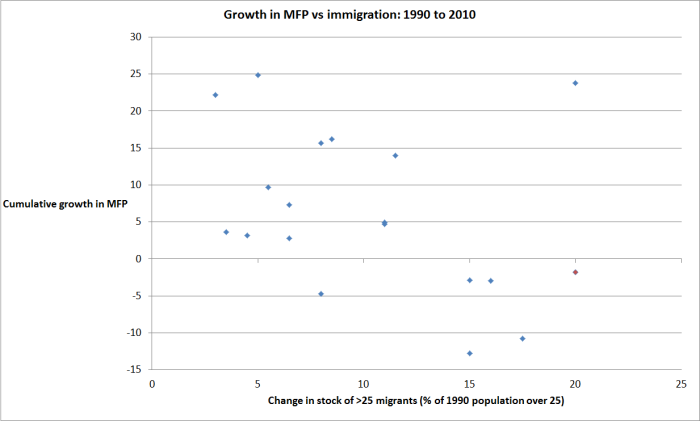

I’ve previously showed simple scatter plots suggesting that the correlation coefficient between immigration – using the immigration data in the previous IMF study – and TFP growth, cross-country, is negative – the outlier in the top right is Ireland, and as this post illustrated, Irish immigration growth came several years after its TFP surge.

As I said, this new IMF work isn’t a New Zealand specific result. But it might have been nice if the IMF authors, in a New Zealand focused paper, had included a chart or table highlighting how New Zealand’s experience compares to the average finding. For example, of the countries in the study, only Luxembourg had higher net immigration (as a share of population) over the same period, and over the period we’ve had moderate per capita income growth, very weak labour productivity growth (third lowest of these countries over this period) and pretty disappointing TFP growth by international standards. You would have to suppose that we look like an outlier (relative to this model, over this period). Of course, there may be others things at work – a relatively simple model like this can’t capture everything – but if you are an international agency wanting to use international research findings to buttress a policy choice of a New Zealand government, surely you owe it to readers – whether interested citizens, or officials and politicians – to provide some detail on how New Zealand’s experience looks to compare to the general results of your model.

As I’ve said repeatedly, I’m quite comfortable with the idea that migration at some times and in some places will benefit natives of the receving country/region. These particular results aren’t that encouraging on the score (no productivity gains on average), even for the larger group of advanced countries as a whole in modern times. But if migration benefits natives economically in some times and places – as it no doubt did in 19th century New Zealand – there is no reason why that automatically translates to a conclusion that all cross-border migration anywhere and at any time is beneficial. In fact, even in this study, a finding of no productivity gains (labour or TFP) across the whole sample must mean that, even if the model is robust, some countries will have had positive experiences and others negative. My suggestion is that New Zealand’s has been negative. Nothing in the IMF results challenges that.

Having said that, it was good to have the work done. I hope the authors considered extending or refining it, and if they are still working on New Zealand issues to drawing out more explicitly how New Zealand’s experience is best explained.

The most important aspect of immigration is to lessen the need for a war. The problem with a closed border is that people of a particular nation would rape and pillage the resources of another nation in its own self interest. People that see each other differently dehumanise and debase another nations people. Closed borders encourage wars. Open borders reduces the need for war as all people are treated equal irrespective of race, religion and colour. Open borders found favour after World War 2.

LikeLike

Not sure about that generally story at all. Just to take NZ as an example, the influx of Anglo settlers in the 19thC was, ultimately, the cause of the very costly Maori/Land wars.

Historically, the great age of advanced country migration was pre World War One (there was the Americas and Australasia to fill). From around WWI until perhaps 30 years ago, immigration was pretty small, at least outside NZ, Australia, Canada, and Israel with some post-colonial large movements thrown in, both former colonists (French returning from Algeria, Portugese from SOuthern Africa) and inflows of natives from colonies (eg to Holland or the UK).

LikeLike

Productivity seems a worthy goal but ‘who’ gains is also somewhat interesting:

Click to access labor-compensation-and-labor-productivity-recent-recoveries-and-the-long-term-trend.pdf

Still, I guess with flexible labour markets and (relatively) equal opportunity to set up a business, no harm done…

LikeLike

I’d say productivity growth is a necessary but not sufficient condition for a better standard of living. It is a good start though.

LikeLike

Or would be if we had had any in the last five years……

LikeLike

Whos had growth in the last 5 years? If I recall there was a significant world event in 2007 bought on by the failure of the Reserve Bank system around the world, its called irresponsible credit creation.

“leveraging the benefits from high net migration” that’s easy one to answer, building our infrastructure, of course.

Its a model I personally would not put too much weight on its conclusions, viz climate change mathematical models, other mathematical economic models, the Reserve Banks own economic model of NZ.

LikeLike

A “robot tax” for businesses replacing workers with automation could become a reality in New Zealand, according to legal experts.

“We have relied on labour and wages to drive consumption and we’re not going to have that – in terms of technological unemployment, even if it gets close to the predictions it would be catastrophic,” said Gregory Marston, head of the School of Social Science at the University of Queensland.

https://www.newsroom.co.nz/2017/04/19/19714/a-robot-tax-to-save-human-jobs

Perhaps NZ leads the world in ensuring people are working and consuming. No point being overly productive with a robot society that does not add to the colourful fabric of life.

LikeLike