While the award of the Nobel economics prize to Israeli-American economist Joshua Angrist is a great honor for Israel, there is something bittersweet in that we have to share the honor with the US.

Angrist, a native of Columbus, Ohio, made aliyah to Israel in 1982 and spent three years teaching economics at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem before moving back to the US.

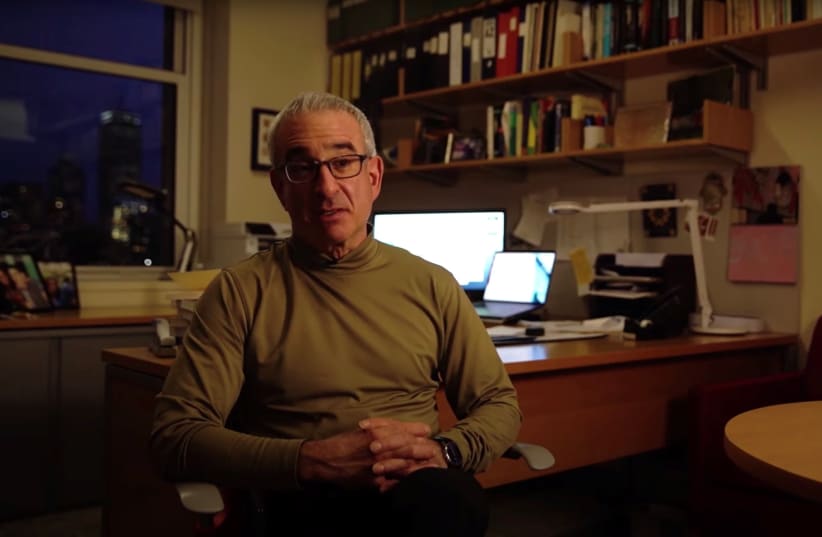

In an interview with The Jerusalem Post in 2006, Angrist explained why he left Israel.

“I was tired of the situation here,” he said at the time. “The Israeli system does not reflect the reality of pay differential by field. It’s the public system, and it’s not very flexible.”

Angrist said he was frustrated that many salaries, particularly in academia, were set using fixed pay grades, with professors in fields such as computer science and economics being paid the same as professors of literature, instead of being set by market forces, as they are elsewhere.

“Talented people who might like to work in Israel have to pay a high price for that financially,” he said at the time. “It’s hard to retain people with that kind of system.”

Angrist isn’t the only one who feels that way. The phenomenon of Israel’s “brain drain,” in which many of the country’s best minds leave Israel for more lucrative opportunities abroad, has been discussed and documented for decades.

In 2019, a report by the Shoresh Institution for Socioeconomic Research found that 4.5 academics left Israel to pursue an opportunity overseas for everyone who returned from abroad. That number had risen rapidly from just three years earlier when 2.6 Israelis left for everyone who returned.

The result is that an “exceptionally small” number of professionals drive Israel’s economy, the report found.

The emigration of Israel’s best talent hurts our hi-tech companies, stresses our medical system and casts doubts on Israel’s ability to maintain its competitiveness in all fields.

This is already a threat to Israel’s red-hot hi-tech sector, which has grown at a breathtaking pace during the coronavirus pandemic. For many newly funded start-ups, flush with tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars of capital, the biggest problem they face is a lack of manpower available to fuel continued growth.

Poor social and economic policies have far-reaching costs that often cannot be easily measured. When Israelis complain about low salaries, high taxation rates, impenetrable bureaucracy and other challenges of life here, we cannot just justify the underlying problems or brush them off. Many people, like Angrist, will not wait around for things to get better.

What could Angrist have accomplished in Israel had he remained at Hebrew University instead of bolting for Boston? It is impossible to say, but it is worthwhile for Israel to think about how we can make sure the next Nobel Prize winner stays here.